Aby Warburg (1866-1929) was a German-Jewish scholar whose research was  focused on iconography, on the legacy of the classical world and on the transmission of classical representation through to the Renaissance. Warburg left a relatively small corpus of writings in German and he did not write anything for the Burlington. He may, therefore, appear to form an unlikely pairing with this journal – and in fact, the writers around the Burlington and Warburg carried forward two distinct, by some even felt as incompatible, fields of scrutiny: iconographic analysis for Warburg and object-based study for the Burlington. If Warburg was concerned with works of art as supporting documents for a wider understanding of cultural history, for many Burlington writers the main focus were the works of art themselves, the circumstances around their creation, authenticity, and their attribution to the rightful artist or artistic tradition.

focused on iconography, on the legacy of the classical world and on the transmission of classical representation through to the Renaissance. Warburg left a relatively small corpus of writings in German and he did not write anything for the Burlington. He may, therefore, appear to form an unlikely pairing with this journal – and in fact, the writers around the Burlington and Warburg carried forward two distinct, by some even felt as incompatible, fields of scrutiny: iconographic analysis for Warburg and object-based study for the Burlington. If Warburg was concerned with works of art as supporting documents for a wider understanding of cultural history, for many Burlington writers the main focus were the works of art themselves, the circumstances around their creation, authenticity, and their attribution to the rightful artist or artistic tradition. Even if ultimately very different, Warburg and many writers of the early Burlington shared similar concerns and even had some history in common.

Even if ultimately very different, Warburg and many writers of the early Burlington shared similar concerns and even had some history in common.

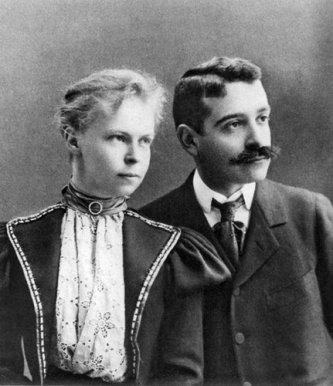

The Burlington was first published in March 1903, when Warburg had just returned to Hamburg and was living and studying there as an independent scholar. Between 1898 and 1902, however, Warburg had lived in Florence, and there he frequented two of the principal founders of the Burlington, Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) and Herbert Horne (1864-1916).

Berenson, Warburg and Horne shared an interest in the Italian Renaissance, especially the Florentine Quattrocento and the painter Botticelli.

Within this shared field, their approach was different. Warburg investigated a broad spectrum of social relations, such as the relationship between artists and their patrons and the economic situation in the Florence of the early Renaissance. The classical past was also a crucial aspect of his studies, for instance, Leonardo da Vinci’s engagement with Vitruvius’ theory of proportion and Botticelli’s relationship with the antique as illustrated by the clothing of figures.

Within this shared field, their approach was different. Warburg investigated a broad spectrum of social relations, such as the relationship between artists and their patrons and the economic situation in the Florence of the early Renaissance. The classical past was also a crucial aspect of his studies, for instance, Leonardo da Vinci’s engagement with Vitruvius’ theory of proportion and Botticelli’s relationship with the antique as illustrated by the clothing of figures.

Bernard Berenson, with his art historian wife Mary Smith (who also wrote with the nom de plume Mary Logan), was then compiling lists of works by Italian painters, identified by artist and by location, with the aim of establishing authorship and thus creating a series of corpora in which his combination of connoisseurship and systematic approach proved immensely successful. Tuscan painters were at the centre of this enterprise. In 1896 Bernard (with the unaknowledged assistance of Mary) had written The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance, followed in 1897 by The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance and by The Drawings of the Florentine Painters in 1903.

In 1894 Horne, who had been commissioned by George Bell & Sons to write a monograph on Botticelli, moved to Italy to study the artist, which he did for 14 years. Horne finally publishing his monograph on this artist in 1908. Horne’s approach was compatible with Berenson’s – focused on the formal qualities, assigning attributions. But Horne’s strength lay also in his ability for archival research, which was solid and stated in a forthright manner.

In 1894 Horne, who had been commissioned by George Bell & Sons to write a monograph on Botticelli, moved to Italy to study the artist, which he did for 14 years. Horne finally publishing his monograph on this artist in 1908. Horne’s approach was compatible with Berenson’s – focused on the formal qualities, assigning attributions. But Horne’s strength lay also in his ability for archival research, which was solid and stated in a forthright manner.

And there lies the connection between the Warburg-based studies and the approach adopted by many writers in the Burlington circle: a close attention to primary sources and emphasis on documentary evidence.

In 2010 Jeremy Melius, writing about Horne’s and Warburg’s approach to Botticelli, noted that they both referred uneasily to the ‘cult of Botticelli’ in their respective countries – Warburg criticising what he called the ‘Botticelli-congregation’ worshipping Botticelli’s ‘Florentine choir-boys’. Similarly, Horne was wary of ‘that peculiarly English cult of Botticelli […] distinctive trait of a phase of thought and taste, or of what passed for such, as odd and extravagant as any of our odd and extravagant age.’ (Horne, Botticelli Painter of Florence, 1980 ed., p. xix). Yet, Melius notes, each of them also belonged to that cult, if only to its last gasps.

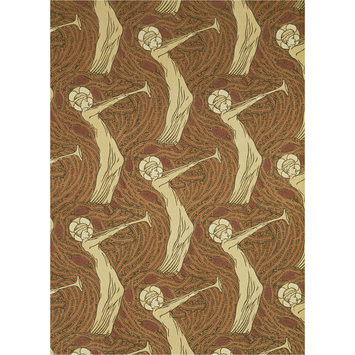

Horne was one of the founders of the Burlington and crucial to the life of this magazine: member of its consultative committee from its start, an assiduous contributor until his death, and designer of its very distinctive typographic layout. Horne was a true polymath: he was a writer, architect, (he designed the chapel illustrated here above), designer and member of the Century Guild, an arts and craft group established in 1883 by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, Selwyn Image and several others, including Horne. Horne then became Mackmurdo’s business partner from 1885 to 1890. The Guild designed applied arts of various types including textiles and upholstered furniture which were manufactured for it by outside firms, including Simpson & Godlee, a textile printing company. Much of this work was commissioned and sold through the Bond Street shop of Wilkinson & Sons.

Horne was one of the founders of the Burlington and crucial to the life of this magazine: member of its consultative committee from its start, an assiduous contributor until his death, and designer of its very distinctive typographic layout. Horne was a true polymath: he was a writer, architect, (he designed the chapel illustrated here above), designer and member of the Century Guild, an arts and craft group established in 1883 by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, Selwyn Image and several others, including Horne. Horne then became Mackmurdo’s business partner from 1885 to 1890. The Guild designed applied arts of various types including textiles and upholstered furniture which were manufactured for it by outside firms, including Simpson & Godlee, a textile printing company. Much of this work was commissioned and sold through the Bond Street shop of Wilkinson & Sons.

Horne also co-edited with Mackmurdo the journal of the Guild, the Century Guild Hobby Horse. This magazine of art and literature ran from 1884 to 1894 and its layout is considered a milestone in British graphic design – Horne, along with the engraver Emery Walker, may have been its creator. Horne was also a collector of exquisite choice and a ‘marchand-amateur’, the early 20th century version of a gentleman dealer, somebody who sold art only semi-professionally. Meeting him in 1888, Bernard Berenson admired the range of Horne’s talents and thought he might become William Morris’s successor, ‘the great man of the next generation’ (E. Samuels, Bernard Berenson, 1979, p. 62).

Horne and Warburg developed a close friendship based on their shared research interest. It is possible to catch a glimpse of their friendly rapport through a few letters preserved in the Warburg Institute Archive in London: they exchanged photographs, articles and ideas in a warm and generous fashion.

In 1902 Warburg wrote to Horne, in German-sounding yet eloquent English, describing their similar research methodology:

‘You [Horne] are one of the few workers in the field who are inclined and able to appreciate the detailed work we have to do, and you have, I am sure, the conviction too that doing the next duty of reading old slips of paper is better than opening large views without having anything real to point out’.

(Warburg Institute Archive: WIA GC/37806 Aby Warburg to Herbert P. Horne, 15/11/1902)

These three positions of approaching works of art, the iconographic (Warburg), the stylistic (Berenson) and the archival (Horne) were soon to polarize into opposite (and conflicting) fields of enquiry, but for a few years there were fruitful exchanges between those scholars.

The relationship between Horne and Berenson deteriorated in the first years of the 20th century and they reconciled only on Horne’s deathbed in 1916, but Horne and Warburg remained friends all their lives – Warburg visited a very ill Horne a few months before his death, occupying only the tiniest rooms in his palazzo: at first Horne was quite frail, but then he was really pleased to talk to Warburg (WIA GC/32643 Aby Warburg to Mary Warburg, 05/02/1915).

As the Burlington sometimes published translations of articles written in languages other than English one may wish that Horne had supported the introduction of Warburg’s writings to British readers, but this was a chance that the magazine, sadly, missed.

BP, September 2015 Writings by Herbert Horne for the Burlington Magazine:

Writings by Herbert Horne for the Burlington Magazine:

1. ‘A Lost “Adoration of the Magi” by Sandro Botticelli’, March 1903, pp.63-74.

2. ‘A newly discovered ‘Libro di Ricordi’ of Alesso Baldovinetti. Part I’, June 1903, pp.22-32.

3. ‘A newly discovered ‘Libro di Ricordi’ of Alesso Baldovinetti. Part II’, July 1903, pp.167-174.

4. ‘Appendix: Documents referred to in Mr. Herbert Horne’s articles on a newly discovered ‘Libro di Ricordi’ of Alesso Baldovinetti, pp. 22 and 167’, August 1903, pp.377-390.

5. ‘Notes on Pictures in the Royal Collections. Article VII-The Quaratesi Altarpiece by Gentile da Fabriano’, March 1905, pp.470-475.

6. ‘Andrea Dal Castagno. Part I-His Early Life’, April 1905, pp.66-69.

7. ‘Andrea dal Castagno’, June 1905, pp.222-233.

8. ‘Painting by Benozzo Gozzoli’, August 1905, pp.377-383.

9. ‘Notes on Pictures in the Royal Collections. Article VIII-The Story of Simon Magus, Part of a Predella Painting by Benozzo Gozzoli’, August 1905, pp. 277-383.

10. ‘A Newly-Discovered Altarpiece by Alesso Baldovinetti’, October 1905, pp.51-59.

11. ‘Il Graffione’, December 1905, pp. 189-196.

12. ‘Giovanni Dal Ponte’, August 1906, pp. 332-337.

13. ‘Jacopo del Sellaio’, July 1908, pp. 210-213.

14. ‘A Lost Adoration of the Magi, by Sandro Botticelli’, October 1909, pp. 40-41.

15. ‘Notes on Luca della Robbia’, October 1915, pp. 3-7.

16. ‘Botticelli’s Last Communion of S. Jerome’, November 1915, pp. 44-46.

Illustrations

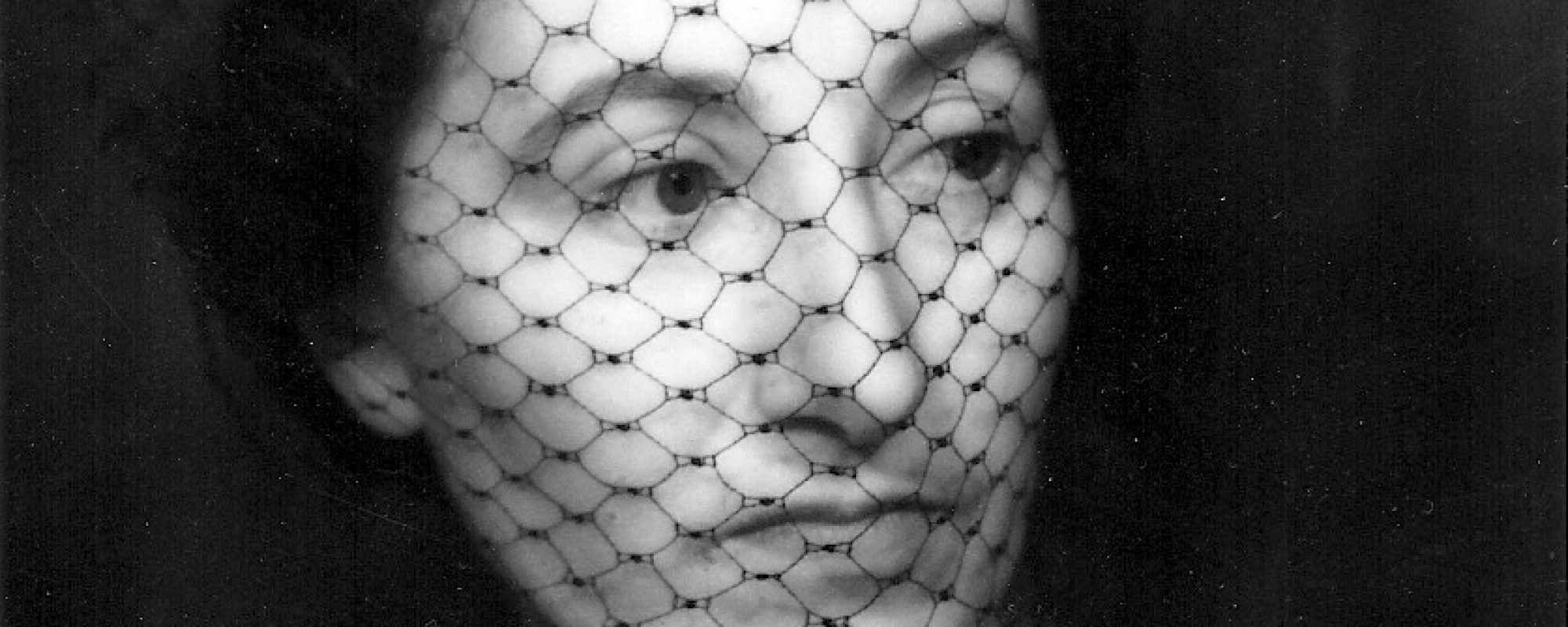

Aby Warburg and Mary Hertz, circa 1900, London, The Warburg Institute Archive.

Henry Harris Brown, Herbert P. Horne, 1908, Florence, Museo Horne.

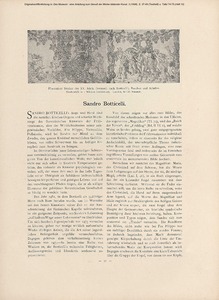

Aby Warburg, ‘Sandro Botticelli’, Das Museum. Eine Anleitung zum Genuß der Werke bildender Kunst, 3 (1898), p. 37.

Herbert P. Horne, Botticelli painter of Florence, cover of the 1980 edition.

Herbert P. Horne, Chapel of the Ascension in Hyde Park Place, Bayswater Road, London, designed in 1889–90, demolished 1969.

Herbert P. Horne, The Angel with a trumpet, fabric design, 1884, London, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Further reading

Saxl, Fritz. ‘Three ‘Florentines:’ Herbert Horne, Aby Warburg, Jacques Mesnil’, Lectures, vol. 1. 1957, pp. 331–344.

Alan Crawford, ‘Horne, Herbert Percy (1864–1916)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37570, accessed 29 Aug 2015]

Melius, Jeremy Norman. Art History and the Invention of Botticelli, Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Berkeley, California, 2010, pp. 129-130.

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/98r1q0mq

Codell, Julie, “Horne’s Botticelli: Pre-Raphaelite Modernity, Historiography and the Aesthetic of Intensity,” Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies, v. 2 (1989), 27-41.

Fletcher, Ian. Rediscovering Herbert Horne: Poet, Architect, Typographer, Art Historian (ELT Press, 1990).

Web resources:

Further Readings on Herbert Horne:

Codell, Julie, “Horne’s Botticelli: Pre-Raphaelite Modernity, Historiography and the Aesthetic of Intensity,” Journal of Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Studies, v. 2 (1989), 27-41.

Fletcher, Ian. Rediscovering Herbert Horne: Poet, Architect, Typographer, Art Historian (ELT Press, 1990).

Reblogged this on editorarthistoriography.

Reblogged this on thearthistoryroom.